As noted in my earlier post on Reading and Re-Reading Great Works, one of the books I am committed to periodically re-reading throughout my life, both to improve my understanding of it, the world, and my place in it, is Italian poet Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. I am only doing so at this time because my friend Brendan Cass has decided to read it for the first time and we agreed that it would be fun and productive for us to study and discuss it together, and I will be posting my comments on it here.

As noted in my earlier post on Reading and Re-Reading Great Works, one of the books I am committed to periodically re-reading throughout my life, both to improve my understanding of it, the world, and my place in it, is Italian poet Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. I am only doing so at this time because my friend Brendan Cass has decided to read it for the first time and we agreed that it would be fun and productive for us to study and discuss it together, and I will be posting my comments on it here.

I think that many people's inclination is to read only Inferno, the first third of the Divine Comedy, for any number of reasons. It is, admittedly, the only one that I have ever read multiple times, although I am fortunate to have devoted a semester to the study of the entire book while at the American University of Paris in 1989-90, and I plan on re-reading it in its entirely now. Much of our understanding of Heaven and Hell, not to mention Purgatory, comes not from the Bible, as many would erroneously assume, but from acanonical books like this one. The Divine Comedy can thus help provide us with a much better sense of where our understanding of these concepts originates.

There are many translations available and the one a former AUP professor of mine, Dr. Petermichael Von Bawey, recommended was the translation completed by Dorothy L. Sayers between 1949 and 1962. We had to balance that guidance with a number of other factors, an important one for us being something that was available online so that we could more easily discuss and compare notes on it. With those considerations in mind, we decided to go with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1867 translation, which is available through the Project Gutenberg website. Regardless of which version someone opts to read, this is a very complex text with innumerable historical, religious, and cultural references, and it will be almost impossible for most people to get the as much out of it as possible without availing themselves of companion materials (e.g., Wikipedia's "List of Cultural Reference in Divine Comedy").

There are many translations available and the one a former AUP professor of mine, Dr. Petermichael Von Bawey, recommended was the translation completed by Dorothy L. Sayers between 1949 and 1962. We had to balance that guidance with a number of other factors, an important one for us being something that was available online so that we could more easily discuss and compare notes on it. With those considerations in mind, we decided to go with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1867 translation, which is available through the Project Gutenberg website. Regardless of which version someone opts to read, this is a very complex text with innumerable historical, religious, and cultural references, and it will be almost impossible for most people to get the as much out of it as possible without availing themselves of companion materials (e.g., Wikipedia's "List of Cultural Reference in Divine Comedy"). Difficult as it is in some cases, I have also selected one stanza from each canto as a representative favorite, and explained my choice thereafter.

Canto I

"Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost."

"Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost."

(These are the opening lines of the book and set the tone for a spiritual crisis that might resonate with almost anyone.)

Canto II

Canto II

"I entered on the deep and savage way."

(This brief line of the canto is also its last and, I think, most evocative.)

This is perhaps the least interesting of all the cantos in Inferno, as it is simply an explanation for why Virgil will be accompanying Dante on his journey -- crucial, perhaps, but a bit contrived and certainly dry in light of what is to follow.

This is perhaps the least interesting of all the cantos in Inferno, as it is simply an explanation for why Virgil will be accompanying Dante on his journey -- crucial, perhaps, but a bit contrived and certainly dry in light of what is to follow.

"Inferno Canto 1, Departure for the Great Journey"

and "Inferno Canto 2, Virgil Comforts Dante"

and "Inferno Canto 2, Virgil Comforts Dante"

"There sighs, complaints, and ululations loud

Resounded through the air without a star,

Whence I, at the beginning, wept thereat."

(I think the passage containing the line "All hope abandon, ye who enter in!" would be the more conventional favorite for this canto, but this appeals to me because of the subtle way it points out that this starless place is an utterly alien environment.)

Canto IV

"And more of honour still, much more, they did me,

In that they made me one of their own band;

So that the sixth was I, 'mid so much wit."

(Here Dante is pleased to be accepted as the companion of Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan, much as any of us would love to be recognized by the exemplars of whatever it is we do.)

In this canto, in which Dante descends into the First Circle of Hell, I could almost sense the poet struggling with the statutory nature of Christianity and the idea that the unbaptized must be condemned to a state of Limbo (not to be confused with Purgatory, as these terms are sometimes used interchangeably.)

In this canto, in which Dante descends into the First Circle of Hell, I could almost sense the poet struggling with the statutory nature of Christianity and the idea that the unbaptized must be condemned to a state of Limbo (not to be confused with Purgatory, as these terms are sometimes used interchangeably.)

"Inferno Canto 3, Charon and the Crossing of the Acheron"

and "Inferno Canto 4, the Limbos"

and "Inferno Canto 4, the Limbos"

Canto V

"Paris I saw, Tristan; and more than a thousand

Shades did he name and point out with his finger,

Whom Love had separated from our life."

(I enjoyed this line because it suggests that Dante and Virgil were not in any particular hurry and that their journey through Hell took longer that one might have expected. It also points to Virgil's vast knowledge of the historical figures damned for their carnality.)

This canto covers the Second Circle of Hell and makes mention of numerous historical lovers. But is Achilles there because of his affections for Briseis or Patroclus? Considering the contemporary attitude toward "sodomites" and the special place for them somewhat deeper down, one must assume the former ...

Canto VI

This canto covers the Second Circle of Hell and makes mention of numerous historical lovers. But is Achilles there because of his affections for Briseis or Patroclus? Considering the contemporary attitude toward "sodomites" and the special place for them somewhat deeper down, one must assume the former ...

Canto VI

"In the third circle am I of the rain

Eternal, maledict, and cold, and heavy;

Its law and quality are never new."

(This line appealed to me as poignantly summing up the fixed nature, monotony, and gloom of the netherworld.)

This Canto describes Dante and Virgil's descent into the Third Circle of Hell, where the gluttonous are torn to pieces by the monstrous Cerberus. While Cerberus is portrayed in Classical myth as a terrible three-headed hound, I was struck to note that Dante gives the beast anthropomorphic qualities here, referring to a black, unctuous beard and clawed hands! One can almost envision a looming, demonic, three-headed werewolf ... It was also interesting to note that Virgil pacifies the beast by throwing handfuls of damp earth into its mouths, which seemed to me as it it were a magical incantation of some sort, as feeding a hungry carnivore mud is not likely to satisfy it or, for that matter, even dissuade it from attacking.

"Inferno Canto 5, Minos"

and "Inferno Canto 6, Cerberus"

Canto VII

"'Pape Satan, Pape Satan, Aleppe!'

Thus Plutus with his clucking voice began;

And that benignant Sage, who all things knew ... "

"'Pape Satan, Pape Satan, Aleppe!'

Thus Plutus with his clucking voice began;

And that benignant Sage, who all things knew ... "

(These opening words to Canto VII seem especially menacing and suffused with evil, invoking as they do the name of Satan, and are all the more ominous in that their precise meaning is unclear.)

In this canto Dante and Virgil pass the infernal being Plutus in their continued descent into the netherworld and, once again, the ancient Roman sage appears to employ divine magic in response to a threat of being impeded, rebuking the dark personage with words that knock it to the ground. They then go on to watch the miserly and the profligate duel each other with great weights, presumably reminiscent of ones that would have been used to measure commodities of various sorts. Virgil gives here a speech about the role of Fortune in the rise and fall of nations (words that ring as true now as when Dante penned them seven centuries ago).

Canto VIII

"My Guide descended down into the boat,

And then he made me enter after him,

And only when I entered seemed it laden.

Soon as the Guide and I were in the boat,

The antique prow goes on its way, dividing

More of the water than 'tis wont with others."

(I have included two consecutive stanzas here, as they both appear to reflect a rudimentary interests in physics on the part of the author and speak to the physical characteristics of Hell.)

And then he made me enter after him,

And only when I entered seemed it laden.

Soon as the Guide and I were in the boat,

The antique prow goes on its way, dividing

More of the water than 'tis wont with others."

(I have included two consecutive stanzas here, as they both appear to reflect a rudimentary interests in physics on the part of the author and speak to the physical characteristics of Hell.)

In this canto the two companions pass over the body-filled swamp of the Styx, ferried in a small vessel by infernal boatman Phlegyas. One interesting thing this chapter of the book confirms is that Dante really is in physical peril while in Hell and that Virgil is not just his guide but also his bodyguard.

"Inferno Canto 7, the Avaricious and the Prodigal"

and "Inferno Canto 8, the Angry Ones"

Canto IX

Was conjured by that pitiless Erictho, "True is it, once before I here below

Who summoned back the shades unto their bodies."

(This revelation by Virgil points to a number of interesting things, including the possibilities of human interaction with spirits and how they might be summoned and constrained to perform various tasks, as well as the way that knowledge of the infernal and celestial planes might be obtained and used by the living.)

This canto picks up at the gates of Dis, entrance to which the companions have been denied and where they are menaced by the three snake-and-cerastes-haired Furies/Erinnys, Megaera, Alecto, and Tisiphone. Virgil summons divine aid at this point and the celestial being that answers his call displays all the alacrity, professionalism, and detachment of a fighter pilot being called in for an airstrike, forcing open the gates and then departing immediately without any extraneous interaction.

"Whence I to him: 'The slaughter and great carnage

Which have with crimson stained the Arbia, cause

Such orisons in our temple to be made.'"

(This appealed to me as an especially poetic reference to the Battle of Montaperti and the subsequent Guelph vindictiveness toward the Ghibelline party.)In this canto Dante speaks with the shade of Farinata degli Uberti, a leader of the Ghibelline party, which was opposed to his own Guelph party and brutal in its interactions with it. Here we learn that the damned can obtain glimpses of the future, even though they do not know what is happening at the present time on Earth (although it took reference to a number of secondary sources for me to sort out this revelation and understand it). Farinata also says "But fifty times shall not rekindled be the countenance of the Lady who reigns here, ere thou shalt know how heavy is that art," but I am somewhat confused as to who he is referring to and by "here" whether he means the Inferno or Florence. One fun detail beyond all this is the purpose of the tombs in which the heretics are confined; as these were Epicureans who denied the existence of an afterlife, even in the otherworld they are presented as being especially dead.

"Inferno Canto 9, the Furies (aka Erinyes)"

and "Inferno Canto 10, the Heretics"

Canto XI

""

In this canto the companions rest before descending further into the depths of Hell and Virgil takes the opportunity to describe to Dante the geography and inhabitants of the next three levels they will enter, the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Circles.

"Inferno Canto 11, On the Edge of the Seventh Circle"

and "Inferno Canto 12, the Minotaur"

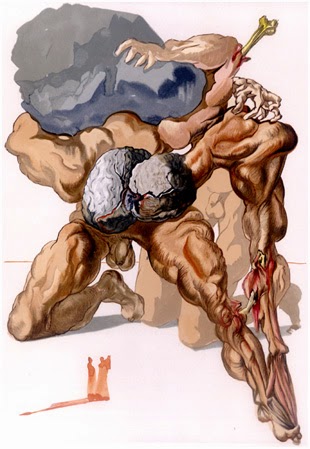

A Note On Art I have decided to illustrate this piece with the series of watercolors that Salvadore Dali began as a commission from the government of Italy in the early 1950s and completed around 1960, and I have identified each of the pieces accordingly. While a series of etchings by Gustave Dore for the Divine Comedy is much more conventional and accessible, I think surrealism lends itself well to the subject of other places of existence. I also own lithographs of six of the Dali images, two from each section of the book, and am thus somewhat partial to them.

I have decided to illustrate this piece with the series of watercolors that Salvadore Dali began as a commission from the government of Italy in the early 1950s and completed around 1960, and I have identified each of the pieces accordingly. While a series of etchings by Gustave Dore for the Divine Comedy is much more conventional and accessible, I think surrealism lends itself well to the subject of other places of existence. I also own lithographs of six of the Dali images, two from each section of the book, and am thus somewhat partial to them.

1 comment:

I m italian and lover of DIVINA COMMEDIA. I do believe to be lucky just because I can understand only reading it without translation. That s great because you can hear the sound that comes out the words like Dante has imagined and created it, the sound that DIVINA COMMEDIA has got from 700 years.

Post a Comment